Student: Show-and-Tell today?

Professor (grinning): Yea. I get to uncover the history of the General Fatigue and Leg Fatigue symptom clusters.

Student: But I was really hurting during the weekend runs. My legs are heavy as lead and sore deep down to the bones. Why?

Professor: Hey, you are not alone. Here is what a former Olympian described being in a tough race:

“Legs are burning. Lungs are searing. …. muscles are dying. … The body is trying to pull the mind away from what it should be concentrating on. That’s really a big struggle.” [Kress & Statler, 2007]

Student: Okay, a foolish question, “What’s the purpose of these pesky hurts?”

Professor: An excellent question about symptoms. Please check out this website’s page: What’s happening? The page discusses the differences between “Symptoms” and “Signs”.

- Symptoms serve as signals in an early warning prevention system.

- They are signals used for self-biofeedback, so one will not ‘go out’ too fast and ‘hit the wall’.

Student: How did you get started on all this?

Professor: I was very curious and sometimes in the right place at the right time.

Student: Also weren’t you a national class marathon runner?

Professor: Yup, and

- I was curious about how my brother, Karl, and I could run faster than 2 hours, 30 minutes for a marathon.

- Also, in 1968, I was assigned as an Army Physiologist to the Medical Research and Nutrition Laboratory in Denver.

- In the same lab, Bob Kinsman and staff had just created the High Altitude Symptom Questionnaire.

- Bob helped me and others do the same for the symptoms of prolonged exercise.

Student: A cookie cutter approach, huh?!

Professor: Hardly. First, Dr Kinsman, a psychologist, had to learn me about personal communication. That is,

- A key presumption is that all athletes use a form of private speech (or “self-talk”).

- Their processing of a self-dialog of questions and answers will occur throughout an event; be it a training session, time trial, or, a race.

- Many athletes have experienced that this on-going dialogue allowed a sense of control within unpredictable unfolding of the event itself.

- A self-administered questionnaire can be built based on self-talk.

- Each individual item will be based upon an answer to the question, “At end of a long event, what are you aware of? Physically. Mentally. Emotionally. Socially.

Student: Then what happened.

Professor: After coffee and donuts, I remember us searching for physical activity items. Here was our initial list:

Table I4-VI Items presented in the Initial Adjective List*

1. Perspiring 22. Determined 43. Happy

2. Short of Breath 23. Comfortable 44. Headache

3. Muscle Tremors 24. Leg Cramps 45. Pleased

4. Test Attention 25. Working Hard 46. Distracted

5. Weak 26. Hard to Breathe 47. Head Tightening

6. Easy to Think 27. Easy to Concentrate 48. Nauseated

7. Physically Tired 28. Leg Twitching 49. Meter Attention

8. Leg Aches 29. Drive 50. Jumpy

9. Lively 30. Heart Pounding 51. Dizzy

10. Weary 31. Refreshed 82. Listless

11. Out of Gas 32. Tired 53. Satisfied

12. Rather Qui t 33. Weak Legs 54. Depressed

13. Aching Muscles 34. Drained 55. Abdominal Cramps

14. Lazy 35. Do Something Else 56. Tense

15. Bored 36. Shaky Legs 57. Irritable

16. Sore from Sitting 37. Hard to Keep Going 58. Backache

17. Heavy Legs 38. Vigorous 59. Angry

18. Numb 39. Dry Mouth 60. Fidgety

19. Easygoing 40. Panting 61. Active

20. Worn Out 41. Sweating 62. Worried

21. Thirsty 42. Fed Up 63. Drowsy

*Items 1 to 41 inclusive were retained for the Modified Adjective List (From Kinsman et al., 1973).

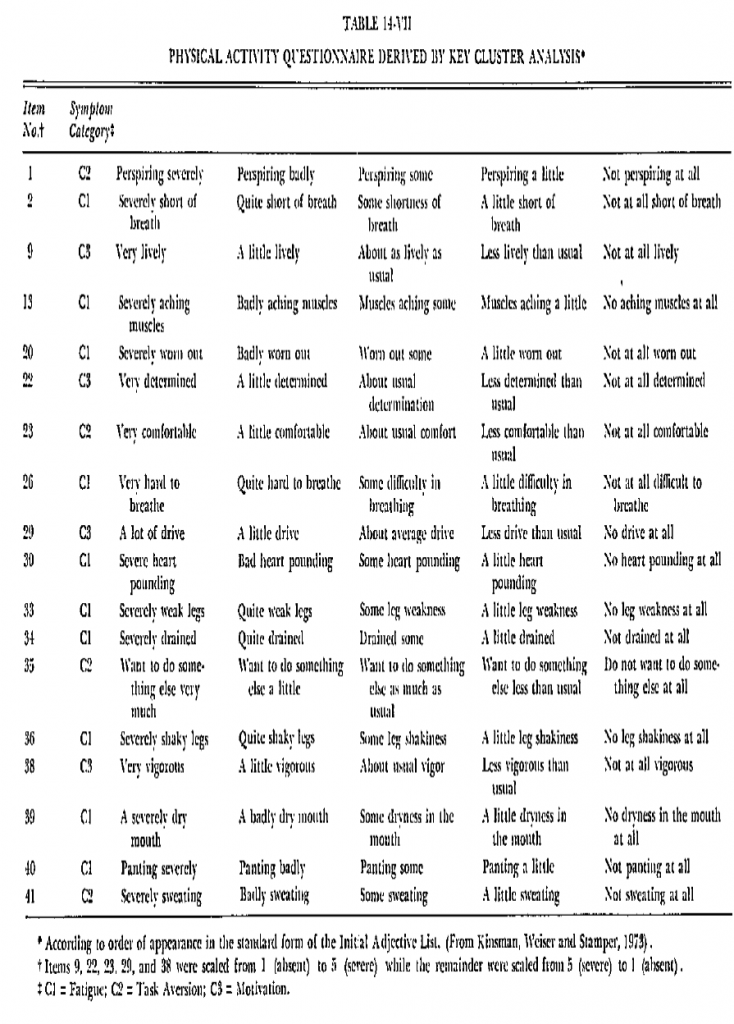

Professor: Now for the not-so-fun part: each of the first 63 items got put on a 5 point scale, adjectives added, some items reversed, and then packed into a multi-page physical activity questionnaire (PAQ) like this:

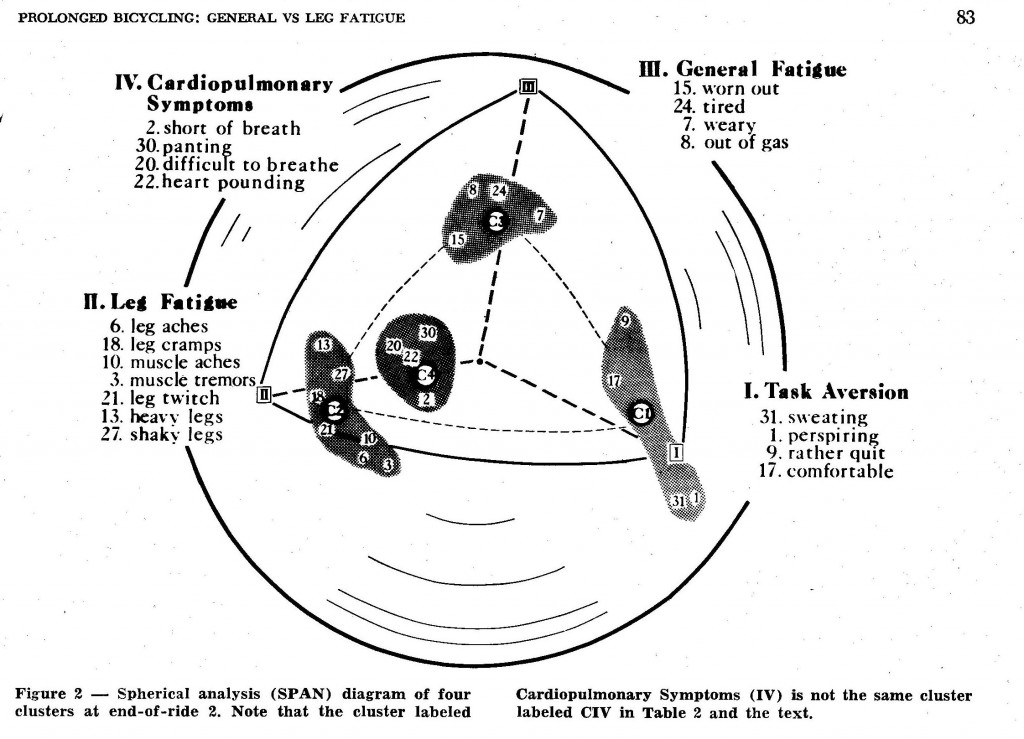

Professor: Next was a pilot study that led to an approved grant. Then, the real study was done, and the data analyzed to remove items that were redundant and/or changed less than 10 percent. Finally, we did the Key Cluster Analysis, and the results are shown on the diagram below:

Professor: We were very pleasantly amazed at which symptoms did group tightly together. And even more so astounding was how the clusters were interrelated. Just look at how far apart are General Fatigue, Leg Fatigue, and Task Aversion (the Motivation cluster was not pictured on this sphere); yet the Cardiopulmonary cluster was oriented neat but separate from the Leg Fatigue symptoms. For more details on cluster internal consistencies etc., download the first published article: Kinsman etal Multidimensional analysis of symptomatology 1973. For information on separating Leg Fatigue and General Fatigue symptoms, download the second published article: Weiser etal Task-specific symptomatology prolonged cycling 1973.

Student: And did the participants’ reports actually show much of a change?

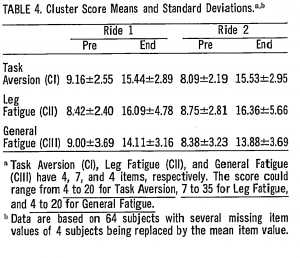

Professor: Not much of a change was reported for Motivation symptoms. However, here are the sums for scale scores for other clusters:

Student: Please note the range of scores for each cluster. Thus for Ride 2,

- Task Aversion went from 25.6% range at Pre to 72.1% range at End,

- Leg Fatigue went from 6.3% range at Pre to 58.5% range at End, and

- General Fatigue went from 27.4% range at Pre to 86.8% range at End.

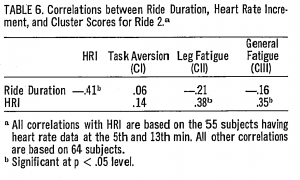

Professor: And the cluster scores were somewhat associated with standard performance measures. Heart Rate Increment (HRI) was calculated as the mean difference in heart rates at the 5th to 13th minute of each ride. HRI and ride duration were compared to each other and to the cluster scores as shown in the table below:

Professor: This was very important Ride duration was negatively correlated with HRI. That is, participants with a longer ride time tended to incur a smaller HRI early in the ride than those with a ride of shorter duration. Also there were positive associations of HRI and the score for Leg Fatigue and for General Fatigue. Could these associations be hints at the mechanism(s) for fatigue during prolonged exercise, I wonder!?

Student: In our heads, then, these hurts, pains, and other discomforts aren’t haphazard.

Professor: Yes, they are not haphazard. Instead they may be very informative.

Take Home Message: Aches and pains form clusters in our feelings and may well be linked to the mechanism(s) limiting prolonged exercise.

Next: An organizational schema is presented that combines subjective symptoms, the physiogical substrata, and the relationship between physiological factors and symptomatology during work. This study was repeated while collecting cardiopulmonary and electromyographic measures. The next post will review the schema and this newer study, then reflect on later published world-wide research.

References:

Kinsman RA, Weiser PC, Stamper DA. (1973) Multidimensional analysis of subjective symptomatology during prolonged strenuous exercise. Ergonomics l6: 221-226.

Kress JL, Statler T. (2007) A naturalistic investigation of former Olympic cyclists’ cognitive strategies for coping with exertion pain during performance. J Sports Behavior 30: 428-452.

Weiser PC, Kinsman RA. Stamper DA. (1973) Task-specific symptomatology changes resulting from prolonged submaximal bicycle riding. Med Sci Sports 5: 79-85.