SUMMARY: “In general, dynamic stretching before you train and static stretching after you train is a great way to warm[-]up and cool[-]down. By taking the time to warm[-]up and stretch before any workout, you’ll minimize the chance of injury.” (Obadike, 2014)

Professor: In addition, here are some myths revealed by questions in a column by Sonya Collins (2014). She wrote,

- “Do any of these lines sound familiar?”

- “You have to hold a stretch [for a long time]to get the benefit.

- “Don’t bounce in the stretch — you’ll tear your muscle.

- “If you don’t stretch before a workout, you’ll hurt yourself.”

- And she replied, “Well, they’re all wrong. But first, there’s a bigger question to answer”

“Do You Need to Stretch at All?”

Student: It sounds like she is really asking, “Is stretching okay?” Or is she questioning, “is stretching counter-productive?”

Professor: And my answer is, “Stretching is helpful only when done

- “at certain times,

- “with finesse, as an adept, practiced skill.”

Student: I can certainly tell that I have not stretched for a while!

Professor: Bob Anderson (1980) liked to say that, “The 1970s have brought us a critical awareness of the necessity for a healthy life.” Injuries many times happened in persons who had ‘tight’ muscles. He wrote that “[stretching] is the important link between the sedentary life and the active life.” He encouraged everyone to use a stretching routine to

- increase flexibility after sleeping and after sitting for a long while and to

- increase range of motion to reach far and wide.

Student: Here is another Sonya Collins kind of question:

“Should I always stretch before exercise?“

Professor: That’s where finesse fits into our fitness routines.

Student: What’s this? Finesse??

Professor: Yup. You got to utilize physical and mental trickery. The use of finesse is an adept, practiced skill!

- Dynamic warm-ups prior to exercise.

- Myth: Hold stretch for long time before physical activities like exercising, training, and competing.

- Fact: Smooth movements, including a mild bounce, makes use of

- contracting muscles (agonists) are

- pulling and stretching opposing muscles (antagonists) that are

- relaxing and uncoiling.

- Static stretches are used during active rest.

- Myth: Endure the pain

- Fact: Stretch until a bit painful and then back off until the pain level is just uncomfortable.

Student: I get it. Static stretching you can save for ‘getting the kinks out’ some other time in the day.

Professor: in fact, I like to do a little stretching after a workout and much more either earlier in the morning or later in the evening. In this way, I incorporate stretching into my Yoga practice.

Student: Now the following question confuses me:

“What kinds of stretching are okay for endurance athletes?“

Professor: First let’s start with the concept of ‘Warmup.’ Dynamic stretches are an essential component for raising muscle temperature and lengthening structural proteins of our muscles and joints.

Student: Okay, and like how?

Professor: Again warm-up is done with finesse, using a combination of the following and other activities:

- Light running (e.g., jogging),

- Easy walking lunges,

- Short heel walks,

- Very brief, repeated sprints,

- Followed by your harder endurance workout.

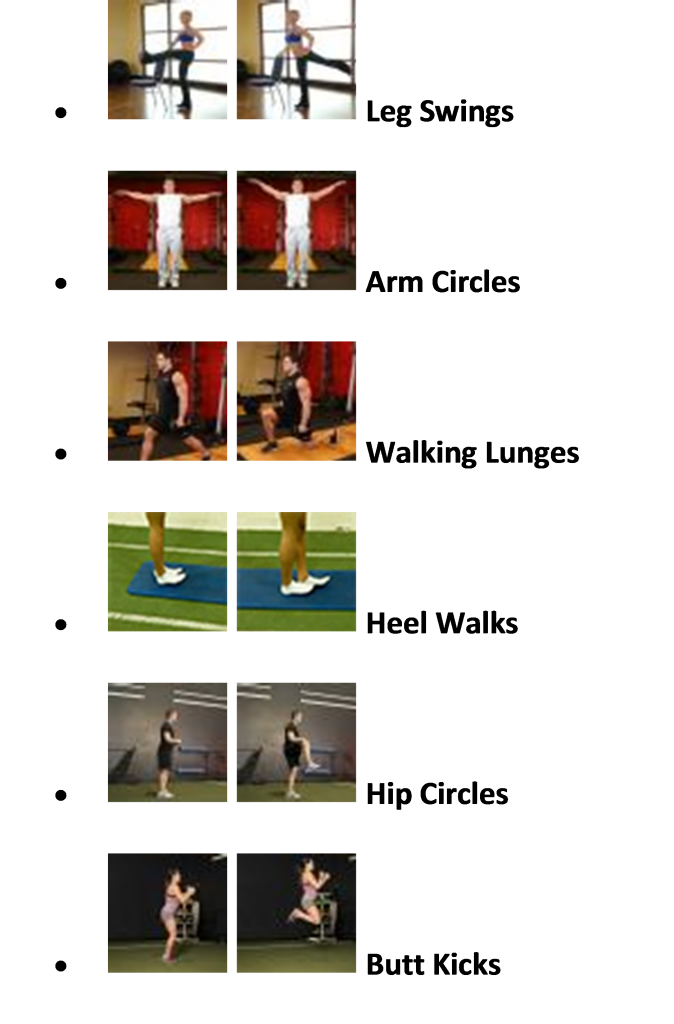

Professor: Below are some examples from Obadike (2014):

Professor: Notice these dynamic stretches incorporate ‘natural bouncing,’ for example, walking lunges. For videos of these exercises, go on his web page: Should I stretch before my workouts, scroll down, and click the links.

Professor: Also flexibility and range of motion can be enhanced using proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation (PNF). Typically PNF involves an isometric contraction of the target muscle–tendon group followed by a static stretching of the same group (i.e., contract–relax) (Sharman et al., 2006).

Student: Hey! I use that technique to loosen up my hamstrings. And what do the ‘experts’ say about all this?

Professor: I guess you mean the academics. Let’s begin by looking at themore recent American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) Position Stand (2011) on exercise counseling of apparently healthy adults. It stated:

- “Crucial to maintaining joint range of movement, completing a series of flexibility exercises for each of the major muscle–tendon groups (a total of 60 s per exercise) on ≥ 2 [days per week] is recommended.”[Abstract on p. 1334]

- “Holding a stretch for 10–30 s at the point of tightness or slight discomfort enhances joint range of motion, with little apparent benefit resulting from longer durations..” [Flexibility section on p. 1344]

- “Older persons may realize greater improvements in range of motion with longer durations (30–60 s) of stretching. The goal is to attain 60 s of total stretching time per flexibility exercise by adjusting duration and repetitions according to individual needs..” [Flexibility section on p. 1344]

- “The exercise program should be modified according to an individual’s habitual physical activity, physical function, health status, exercise responses, and stated goals.”[Abstract on p. 1334]

[Outlining and page referencing added]

Student: In general, the articles by Obadike (2014) and Collins (2014) are consistent with this statement, but the ACSM Position Stand is less specific.

Professor: Concerning negative results of stretching, McHugh and Cosgrave (2010) have stated in their review that,

- “There is an abundance of literature demonstrating that a single bout of stretching [when employed as part of a warm-up] acutely impairs muscle strength, with a lesser effect on power.”

- “Interestingly, stretch-induced strength loss … is, in part, attributable to a prolonged inhibitory effect of stretching (Avela et al., 1999).”

Professor: To emphasize this impairing, negative effect, the ACSM Position Stand (2011) also included this statement:

- “Stretching exercises can have a negative effect on subsequent muscle strength and power and sports performances, particularly when strength and power are important.” [Flexibility section on p. 1345]

[Page referencing added]

Professor: Recently four important academic articles on stretching and power performance strengthen the ACSM Position Stand.

First, Simic et al. (2013) used a meta-analytical approach to estimate the acute effects of pre-exercise static stretching (SS) on strength, power, and explosive muscular performance.

- “A total of 104 studies yielding 61 data points for strength, 12 data points for power, and 57 data points for explosive performance met our inclusion criteria.

- “[The acute, detrimental] effects were … more pronounced in isometric vs dynamic tests, and were related to the total duration of stretch, with the smallest negative acute effects being observed with stretch duration of ≤45 s.

- “We conclude that the usage of SS as the sole activity during warm-up routine should generally be avoided.”

Second, research by Smith et al. (2014) re-emphasized the importance of warm-up and tested postactivation potentiation (PAP), which is similar to PNF.

- The standardized warm-up consisted of 4 min of pedaling on a stationary cycle followed by 4 min of active rest slowly walking around a track.

- The control trial consisted of a pretest 40-yard (yd) sprint, 4 min of active rest, a 20-yd sprint (i.e., a PAP stimulus), 4 min of active rest, and the posttest 40-yd sprint.

- After these warm-up activities, the speed in the post-test 40-yd was faster.

- They also had experimental trials substituting the 20-yd PAP sprint with a 20-yd resistance sprint pulling a sled with additional weights totaling 10%, 20%, or 30% body weight; the increased post-test speed was similar to the control (no sled) trial.

Third, a study by Bingul (2014) examined the importance of a recovery time after static stretching for preventing loss of hamstring peak power.

- After 5 min of jogging, three hamstring static stretches were each held for 30 sec and the set was repeated; after varying times, hamstring peak power was measured.

- The sensations during each of the stretches were not stated.

- Recovery times of 6 and 9 min restored peak power, but not for 3 min recovery.

- Optimal recovery time was between 3 and 6 min, which has been used in other studies; for example, 4 min was used by Smith et al. (2014).

Fourth, Mascarin et al. (2015) tested ball throwing performance by female handball athletes.

- Static stretching was done to a threshold of mild discomfort, and each stretch lasted for 30 sec.

- Each dynamic stretch was repeated 8-10 times (one repetition per sec).

- SS performed prior to the medicine ball throwing test reduced performance when compared with the dynamic warm-up exercises.

- When the dynamic warm-up exercise routine was added to SS, the detrimental effects of SS were abolished.

- The ball throwing test was done after the medicine ball throw; the ball speed was the same over the three conditions.

- Therefore, the investigators recommended that “athletes perform [dynamic] warm-up exercises, together with static stretching, prior to activity to avoid detrimental effects on muscle strength.”

Student: And here is the final question:

“Do I have to hold the stretch for a long time?“

Professor: To repeat, for static stretching, only 10 seconds or less is enough to unkink structural proteins that hold muscles, tendons, and joints together.

- Overstretching can be harmful.

- First, move into the stretch until a twinge of pain is felt, and

- then, back off until pain changes into a mild discomfort and hold.

- It is more dangerous to not stretch at all and lose range of motion.

- Use contract—relax PAP repetitions or

- accentuate movements as dynamic stretching to regain lost range of motion.

TAKE HOME POINT: Dynamic stretches is an important part of warm-up routine; static stretches is a major component of alternative time for getting out kinks or regaining lost range of motion.

NEXT: Completion of the series on Sensory gating and processing of fatigue/exertion related symptoms of Systemic Exertional Intolerance Disease (i,e, Chronic Fatigue Syndrome).

References:

American College of Sports Medicine. (2011) Position Stand: Quantity and Quality of Exercise for Developing and Maintaining Cardiorespiratory, Musculoskeletal, and Neuromotor Fitness in Apparently Healthy Adults: Guidance for Prescribing Exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc 43: 1338-1359. DOI: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318213fefb.

Note: This Position Stand replaces the 1998 ACSM Position Stand ‘‘The recommended quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory and muscular fitness, and flexibility in healthy adults,’’ Med Sci Sports Exerc. (1998) 30(6):975–91.

Anderson B. Stretching. Bolinas, CA, USA. 1980, p 8.

Avela J, Kyröläinen H, Komi PV. (1999) Altered reflex sensitivity after repeated and prolonged passive muscle stretching. J Appl Physiol 86: 1283–1291.

Bingul BM. (2014) The optimal waiting time for hamstring peak power after a warm-up program with static stretching. Anthropologist, 18: 777-781.

Collins S. (2014) “The Truth About Stretching. Find out the best ways to stretch and the best times to do it.” http://www.webmd.com/fitness-exercise/guide/how-to-stretch

Mascarin NC, Vancini RL, Lira CA, Andrade MS. (2015) Stretch-induced reductions in throwing performance are attenuated by warm-up before exercise. J Strength Cond Res. 2014 Nov 25. [Epub ahead of print] DOI: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000000752

McHugh MP, C. H. Cosgrave CH. (2010) To stretch or not to stretch: the role of stretching in injury prevention and performance. Scand J Med Sci Sports 20: 169–181. DOIi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2009.01058.x

Obadike O. (2014) “Should I stretch before my workouts?”

http://www.bodybuilding.com/fun/ask-the-ripped-dude-should-i-stretch-before-my-workouts.htm

Sharman MJ, Cresswell AG, Riek S. (2006) Proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation stretching: Mechanisms and clinical implications. Sports Med 36: 929-939. DOI: 10.2165/00007256-200636110-00002

Simic L, Sarabon N, Markovic G.( 2013) Does pre-exercise static stretching inhibit maximal muscular performance? A meta-analytical review. Scand J Med Sci Sports 23: 131–148. DOI: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2012.01444.x